only magazine

↵ home

Condemned Housing

By Sean Condon

Tuesday August 7, 2007

Residents at the Marie Gomez Look for Reprieve

A few months ago a drug dealer burst inside Calvin Smoker’s bachelor apartment in the Marie Gomez Place and smashed a drug addict’s face in with a metal pipe. Blood splattered across the room. A surprised Smoker picked up a two-by-four and chased both of them out of his room, but the dealer still managed to beat the user up pretty badly.

“There’s violence all over the Downtown Eastside,” says the soft-spoken Smoker, who suffers from severe arthritis and has to use a scooter to get around. “There’s people getting killed all the time, you just don’t hear about it.”

The 60-year-old native man was able to get the drug dealer out of his room on that occasion, but over the past three years that he has lived in the Marie Gomez, he hasn’t always been so lucky. Drug dealers have often muscled their way into his room and kicked him out to use it as a base to deal drugs. Sometimes staff at the Marie Gomez were able to help him reclaim his place. But since the building is drastically understaffed, Smoker often had to just sit and wait for them to leave.

Overrun by drug dealers, violence, crime and disease, and crumbling to the point that it has been considered condemned, the Marie Gomez may be the worst building in the Downtown Eastside. Sitting inauspiciously at the corner of Alexander and Princess–at the edge of downtown’s industrial zone–the City of Vancouver is in the midst of shutting the building down and will most likely demolish it by the end of this year. But in the meantime, Marie Gomez residents will continue to live in one of the unhealthiest and most dangerous buildings in Vancouver.

“If these people were cats and dogs, the SPCA would be here and shut this place down,” says Garvin Snider, a former maintenance worker in the building who still volunteers his time by doing repairs, “but since they’re crack heads, it’s OK.”

Like most projects in the Downtown Eastside, the Marie Gomez started out with the best of intentions. Built and operated by the BC Housing Foundation in 1981, the society wanted to expand its outreach into the city’s poorest neighbourhood. But the building had construction problems from the start and has suffered from constant leaking. The society also quickly realized that it was in over its head in terms of dealing with the extreme social problems, and in 1988 sold the building to the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA) for just $1.

But the structural damage and financial problems caught up to the building in 2002 and DERA was forced to shut it down. Although DERA owned the building, the social housing building was operated by CMHC, the federal crown corporation. While the building was shut down, the CMHC did not make any repairs. Frustrated by the government’s inactivity and the growing amount of homeless in the city, DERA reopened the building in 2003 and filled it with tenants who are considered “hard-to-house”.

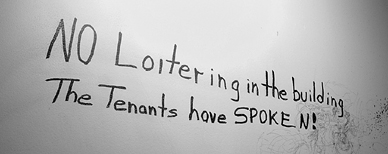

The building’s problems continued to grow as drug dealers took it over, causing a SWAT team to storm the building in 2003 to bring it under control. But the drugs and violence didn’t disappear from the Marie Gomez. Last year, the Province newspaper ran a story about sex workers who live in the building being tortured and having their heads shaved for drug debts–an allegation that DERA has denied. Today, tenants say the violence and drug dealing have calmed down considerably thanks to a new building manager named James Hardie that has chased many of them away. But it may be too late the save the building.

Last April, there were two fires deliberately set in the Marie Gomez. With the building already a virtual tinderbox, DERA was afraid it could have led to massive deaths. The federal government transferred operational authority of the building to BC Housing and the Marie Gomez was put under lock down. BC Housing brought in two security officers to monitor the building 20 hours a day and tenants were told they had 60 days before the building would be shut down. And just when it seemed things couldn’t get any worse, the building suffered two tuberculosis scares. With the health and safety of the Marie Gomez continuing to deteriorate, nurses won’t even enter the building.

“There’s no lights in the building, there’s drug dealing in the halls, there’s rats — it’s been condemned,” says Vivianna Zanoccoa, a spokesperson with Vancouver Coastal Health. “It’s unsafe from a number of standpoints. It depends on the clients, but we try to get them to come into clinics or community centres for treatment… It’s an unsafe situation for the nurses.”

The poor state of the Marie Gomez is especially troubling considering it is one of the few self-contained apartment buildings for low-income residents in the Downtown Eastside. Many of the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels in the area are tiny rooms (roughly 100 square feet) and tenants on each floor share a bathroom and kitchen. But in the Marie Gomez, the rooms are much more spacious and come with their own bathrooms. With the average rent in the Downtown Eastside skyrocketing to more than $400 a month as the neighbourhood gets gentrified, it is one of the few places that charges its tenants just $325 a month.

Despite its numerous problems, Miguel Araiza says the Marie Gomez is the “best place he has ever lived.” An extremely gentle and polite artist, Araiza is bi-polar and has lived in the building for the past three years. He creates some very intricate and beautiful drawings and his room on the first floor is creatively covered in hanging speakers and art projects.

Araiza left Mexico 18 years ago because of human rights violations and when BC Housing brought in security guards that began to harass the tenants, he was frustrated to find human rights violations going on in his own building in Vancouver. And between 4 and 8 am, the security guards don’t work , leaving the building vulnerable to violent and predatory drug dealers. Araiza feels the building could be saved if BC Housing would invest some money and time in fixing the place up, but that seems very unlikely.

Repeated requests for an interview with BC Housing were not returned. However, Cameron Gray, the director of the city’s housing centre says the building is in difficult shape because of envelope failure and leaking from the copper piping. He says he suspects the building will have to be torn down, but will probably hold off on a decision until the city’s review of the Oppeheimer Park area is finished in the fall — although the city strike could affect the timing.

It’s a sentiment that is shared by DERA executive director Kim Kerr. He admits the building is a “shithole” and says the problems keep him up at night. While the rest of DERA’s buildings have a solid reputation, the police answer roughly 100 calls a year to the Marie Gomez. Kerr agrees that the building should be shut down, but says he’s conflicted because of the city’s growing homeless problem. When the Marie Gomez goes down, there will be 50 more people looking for apartments in an already crowded Downtown Eastside. Although the province recently bought 10 SRO buildings in the area, it is currently renovating parts of them, making a scarce housing situation in the neighbourhood even worse. With repairs to Marie Gomez costing roughly $2.5 million and DERA owing $2.4 million in mortgage debts on the building, the association doesn’t have the financial means to keep it running or even properly staffed.

“Frankly, we live in a very rich province and rich country,” says Kerr. “Could the province go up there tomorrow and do the repairs and save the building? Yes they could. And could they go in there and tear the building down and replace it immediately with a new building? Yes, they could do that too. The bottom line is the provincial and federal government have the money to do that. The dilemma for us is that we have people living in a building that doesn’t meet the standards that we would house people in. But with the homeless crisis in the city where are these people going to go?”

That’s the problem now facing the tenants that remain the building. Many do not want to leave, but accept it is inevitable. Considered “hard-to-house”, tenants at the Marie Gomez have a number of extreme health problems and can’t be easily integrated into other buildings. Kerr says every tenant will be relocated before the building is shut down and feels confident that BC Housing will ensure that happens. But there are no guarantees.

What happens to the land after the Marie Gomez is torn down is still up in the air. The city owns the land and once the building goes down, DERA loses its authority on what will replace it. With gentrification continuing to creep in the Downtown Eastside and with the terrible problems the Marie Gomez has endured, the city could use it as an excuse to build condos. To do so would be a travesty to the residents of Marie Gomez who have had to live through horrible conditions just to keep from becoming homeless. When the building goes it will leave behind a truly tragic legacy. The best way to change that would be to rebuild a bigger and better social housing building that would finally give the people of the Marie Gomez the home that they deserve.