only magazine

↵ home

Dissecting the "Twilight"

By kspenst

Tuesday September 11, 2007

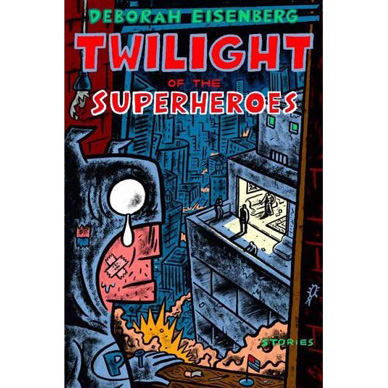

Deborah Eisenberg’s “Twilight of the Superheroes”

It took Deborah Eisenberg eight years to meticulously put together the six short stories which comprise “Twilight of the Superheroes”. Her gorgeous yet tightly wrought blend of poetic-prose, philosophy, politics and humor make the collection a page-turner in both directions.

One of the central conceits running through all six stories is how we organize ourselves through expectations interplayed within time. The titular story that opens the collection begins with a character imagining himself in the far off future. He tells his grandchildren about the miraculous dawn of the new millennium, the giddy excitement that was soon followed by a fear of computers going on the fritz, and an anxiety over questions like: “would all the airplanes in the sky collide?” The fears are replaced by joy over the fact that nothing happened at the end of the countdown to the new millennium. This imagined monologue, steeped in maudlin nostalgia, takes on an irony that becomes pitch black as we read about the main character’s temporary home in New York that overlooks the end of the Twin Towers. We are also encouraged to understand the scene from perspectives outside of America, from “populations ruthlessly exploited, inflamed with hatred, and tired of waiting for change to happen by,” whose expectations have been driven into rage.

But the brilliance of Eisenberg’s writing is that even though it’s chock-a-block with ideas and musings from a variety of characters, she always returns to the familiar. The exploration of how we shape ourselves through time, while occasionally towering up into brilliant tangents of thought, always returns to the tangible. The last story in the collection begins with an older woman in the midst of an affair. “Do we have to be careful about the time?” her lover asks. She doesn’t answer him directly, but rather we become part of her experience: “I reach for my watch from the bedside table and consider the dial — its rectitude, its innocence — then I understand the position of the hands and that, yes, rush-hour traffic will already have begun.”

To top it all off, Eisenberg’s stories can also turn into laughter. In “Some Other, Better Otto” the theme of age, time and perspective are all wrapped up in the main character’s complaint: “Everyone always says ‘Don’t you want to see the baby, don’t you want to see the baby,’ but if I did want to see a fat, bald, confused person, obviously I’d have only to look in the mirror.” Later in the story Otto is interviewed by his nine-year old niece who can only relate to people by talking into her fist and pretending to be a news-reporter. Meaning hides in absurdly hilarious imagery.

In an age of speedy efficiency and pre-fabricated purpose, it’s refreshing to read prose that’s been so carefully put together. The wisdom of looking at life through variegated lenses permeates each page resulting in an aesthetics of honesty that is an integral part of any good writing. It’s only within that honesty that we have freedom to think, because to deny the problematic impact of technology and our politics on the rest of the world would be to develop a habit of evasion. By acknowledging the complexity and confusions of this world, Eisenberg electrifies thought and makes the movements of the mind exciting and vital. At the age of 60, she overflows with wisdom in an interplay of perspectives that leaves you wanting more.