only magazine

↵ home

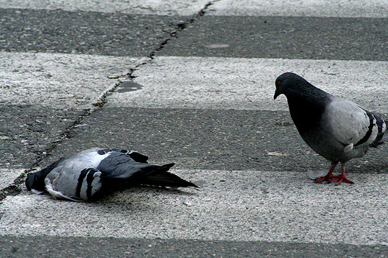

Winged Mutilation

By Alan Hindle

Tuesday December 4, 2007

The first time I killed a pigeon with my bare hands it was an act of heroism.

Actually, the second time I killed a pigeon with my bare hands was also an act of heroism, but the old lady watching, cheering me on, panting supportively, making suggestions – it was upsetting. Unpleasant for the bird, too.

It was years ago. I was young, filled with a love for all things verminous and diseased. Walking along Granville street downtown I passed a crowd facing inwards and staring down at their feet. Curious, I joined the ring.

At the nucleus, pushing itself in pathetic circles, was a pigeon with a broken leg and wing. I watched a while, then finally said, “We’re going to have to kill it, you know.”

The crowd looked at me, nodded, and resumed their vigil over the shivering mess of feathers. I sighed, and picked the poor thing up gently.

Now, my friend Tea grew up on a farm near Prince George. She’d once told me the quickest way to kill a chicken was to twist and break its neck – ZUP! Dead. I took firm hold of its head and gave a sharp turn.

The pigeon hardly noticed, so I gave it another zing. Its good leg kicked feebly in protest, and one wing made as if to leave. It suspected something was up. I gave two more spins, like turning a faucet, until the head had come around 360 degrees. The bird’s bulging eyes had fogged over. Its little beak, a globule of spit and blood collected in each corner, opened to gasp a final breath, and in that final breath I thought I heard the word, “MURDERER…”

I sort of freaked out, giving an involuntary yank that ripped the head clean off. Warm, salty blood streaked up my arm, into my face and gaping mouth. I could taste it, feel the giant, poisonous microbes and bacteria as though they were big as my thumb, crawling about my gums.

I threw down the head, tossed the body into a garbage can and stormed off.

I don’t know what made me turn around. Remorse? Curiosity? I looked back and saw the circle of people look up at me, their eyes screaming ‘Killer!’ The severed head on the ground stared after me, its tiny beak pointing as a final clue to the police which way I had made my escape.

I stumbled into the nearest pizza slice joint. In those days some of these places were pretty rough. However, as I stood there in the doorway, chalky, wild-eyed, streaked with blood, giant microbes slithering between my teeth, the room ogled me in terror.

“I need a bathroom,” I mumbled thickly.

A sea of tattoos and scars parted making a path to the stinking sewer-closet in the back. When I came out I was given two free slices, a can of coke and a subtle hint to leave as I was scaring away customers. Soon after this event, I left the country.

To make a long story shorter, I eventually returned to this country.

My mother had just started dating the man who was eventually to become my stepfather. I was living with her and my two sisters again in a one-room apartment. Being Scots-Irish we possess a genetic propensity to survive being cooped up together, an entire family tree crushed into a bed-sit without loss of dignity. For example, every morning they’d sit outside the toilet listening to me orchestrally farting and when I came out pretend to be absolutely fascinated and engrossed watching bacon cooking.

However, at this time mum and boyfriend were shagging morning, noon and night, so my siblings and I were basically homeless, wandering the streets until we thought it safe to sneak in.

All this is by the by and making a shortened story long again, so I skip to the point.

One afternoon, walking along the sidewalk outside the apartment waiting for the screams to stop emanating from the window, I came across a little old lady staring intensely at a pigeon. The pigeon was broken and shaking with agony. I watched a while, then said, “We’re going to have to kill it, you know.”

“Yes, I suppose we must. But look! There, under the bushes! A kitty cat. Surely it will put the poor creature out of misery.”

“Yes,” I nodded, “but not quickly, or humanely…”

“Oh. No. No, I fancy not.”

The old lady chewed her white gloves fretfully, and the way of things was clear to me. I picked the bird up, cooing sympathetically to calm it down, and started digging for a neck.

Years earlier I had told my friend Tea about the debacle of my last assassination and she just laughed at me.

“Oh Christ! You don’t twist its head! That’s awful! You put your thumbs and fingers on either side of its neck, like this, and give it a sharp jerk – ZAP! Just like that. It’s over in a second. What you did sounds horrible!” she said. Laughing and laughing. Thanks. So now I knew.

I rummaged greasy feathers for a knotted string of gristle I assumed was a neck. You’d be amazed how little neck there is to these things; just a thin bridge between blinking head and fidgeting body. I arranged my lethal fingers there and – ZAP!

The bird winced. It looked confused. Put out, even. Where are the lullabies now, mister?

I snapped again and again, but it was just getting dizzy, not dead. Finally there was nothing else but to put all my strength into crushing its throat.

“Oh,” breathed the little old lady. “You’re doing ever so wonderful a job. I’m so thankful you came along. Yes, that’s it. Oh, oh yes, just a little more and I think you’ve done it. I’m so grateful, really…”

At last I could stomach myself no longer. I hurled down the body, which the cat pounced on before I changed my mind. The old lady thanked me profusely, but I brushed her aside and stalked off.

Sometimes I see pigeons clustered together, and I wonder if they know who I am. If pigeon mothers put their burbling brood to bed with threats that if they don’t go straight to sleep the Pigeon Killer will come and give their delicate pipes a squeeze.