only magazine

↵ home

Judgment of Another Angry Austrian

By Adam Thomas

Sunday April 22, 2007

A bit of a downer at parties

There are two sides to Michael Haneke: the unknown angry Austrian and the more contemporary angry European, known for films like Code Unknown, The Piano Teacher and Cache. But as an Austrian-born filmmaker now making most of his films in French, the constant in his work is the psychological torture he seems devoted to exposing his audiences to as his characters navigate the emotional landmines of murder, sexual depravity, depression and paranoia.

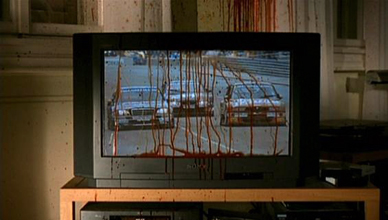

Beginning with a trilogy of sorts, what he calls his “emotional glaciation trilogy” (Seventh Continent, Benny’s Video and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance) represents an early and more formalist approach to cinema, with precise–if not unusual–framing, static composition and painfully long lingering shots of people behaving in totally awful ways. They are a challenge with their inescapable and emotionally numbing vision of the way TV, mass and even personal media affect humanity’s ability to find coherent meaning and compassion. Both Seventh Continent and 71 Fragments are composed of a series of vignettes where characters’ stories are inter-cut with television news segments relating the latest tragedy. Benny’s Video follows a young boy who films a pig being slaughtered and then uses the slaughter gun on a young girl and feels no remorse. This emotional void is the thread Haneke seems content in weaving through all his films: the monkey-see-monkey-do of moral decline.

Haneke’s cinema is art as a cold eye, and he constructs his films with precision and ruthless amoral judgment. With Funny Games, psychological torture is made explicitly physical. When a family goes to the country they end up being held hostage and tortured by two strangers. Like a smart prick cousin to Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange, it plays with our own sense of control and identification. While we wait, bursting with sympathy, for George and Anna during a single ten-minute take as they try to escape, Haneke works to brutalize you too, as the intruders, Peter and Paul speak to the camera, ultimately controlling the transmission.

But it is not just an obvious desire to deflect all personal liability. Haneke’s not sloughing off our failures as being entirely determined by outside influences. Yes things happen that have effects but there’s always a certain amount of the inside that just needs to come out, even if it’s cruel. Haneke’s queasy and wrenching success The Piano Teacher, set in Vienna, is a film to make Freud proud. About a seriously wound up piano teacher (Isabelle Huppert) who rebuffs, then dominates a relationship she has with a young student, it is a devastating exploration into a woman’s sexual repression as she sniffs cum-stained shorts and cuts herself for pleasure? But there is also a sincere “humanness” in the film as Erika’s character is shaped and confused but tragically caught living the life she makes. These behavioral moments are what Haneke seems to think ultimately define us and Code Unknown, an early entry in the multiverse movie category — telling three stories that are connected through a single incident of violence — offers a broader world view where cause and effect are tangible forces but only when acted on by individuals.

None of these movies make for much of a good old popcorn-munching time, and Michael Haneke might be a big downer at a party, but his films are well crafted and undeniably powerful. There’s purpose behind the embittered exercises he forces you to experience–if only to expose the nature of violence and the ways we express our darkest urges. Or just look at it this way, Haneke makes these movies so you don’t have to.

Films of Michael Haneke are playing at Pacifique Cinematheque, April 20 – 26. Check website for showtimes.