only magazine

↵ home

Doxa Film + Video

By Adam Thomas

Friday May 20, 2005

Diary Of A Hostage

The greatest achievement of any film is its continual relevance; to be important and interesting past its contextual release, for it to move from being timely to timeless. It is this capacity that allows the meaning and message of a film to resonate and affect people in the way they live and the way they see the world around them. This year’s Doxa: Documentary Film + Video Festival consists of a strong collection of social and political documentaries, taking us back to our collective past in hopes of showing us a way to live in the future.

In light of Only’s well deserved summer holidays, the rising separatist sentiment in Quebec and the fact that there may well be another Federal election while Only is kicking it poolside, here is one of those films that may well be about Canada’s past, but is equally relevant to its future.

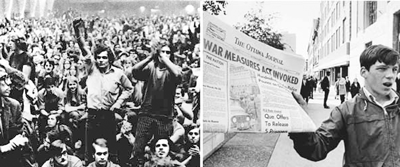

In the fall of 1970 Canada was thrown into social and political turmoil as members of the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ) kidnapped British diplomat James Cross, put forth a series of demands and threatened his execution if the demands were not met. Subsequently, the FLQ kidnapped another man, Pierre Laporte, and with social chaos about to erupt, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau responded by suspending civil liberties and invoked the War Measures Act. This was Canada’s initiation to the modern world of terrorism, a dark period of political crisis where a country and its people were forced to examine the roots of frustration that held the country hostage.

The fundamental cause of this scenario was the struggle for Quebec’s independence, and members of the FLQ saw themselves as the spark that would ignite a cultural revolution.

During the late 1960’s and early 70s Canada experienced a time of possibility. A new generation had come into its own and had elected a new kind of Prime Minister. Art, culture and federalism were all part of the agenda as Canada began to define itself. In Quebec however, there was a growing sense of unrest and alienation as many began to feel that the cultural identity of Quebec was at risk.

Carl Leblanc’s film Hostage is an intimate and unique window into the experience of kidnap victim and former British Diplomat, James Cross. Composed of archival footage and new interviews with Cross — now 80 and living in England — as well as with former FLQ leaders, the film examines the political and personal consequences of a man caught in the crossfire of a cultural showdown. A victim of circumstance, Cross was kidnapped by the FLQ and used as a bargaining chip while they demanded the release of 23 political prisoners, the broadcast of the FLQ manifesto and safe passage to Cuba. But more than simply a historical overview, Hostage gives voice to Cross as he and his family articulate the terror they went through during his 59 days of captivity. His eloquence and even temper are haunting as he revisits a time when he readied himself for a death that could have come at any moment. And despite FLQ leader Jacques Lanctot’s assurance that Cross’s execution was only a bluff, it is all the more frightening listening to Cross talk about the moment when the other hostage Pierre Laporte was found dead in the trunk of a car.

While Hostage is not revolutionary in form, it does offer a rare glimpse into the hearts and minds of both captor and captive, and is only possible because Cross was never killed. In the context of today’s political climate, both here and around the world, it is an important document and memoir on how the struggle for one’s freedom should not be derived through denial of another’s.

The Doxa Festival opens May 24, 2005 at the Vogue Theatre and runs until May 29 at the Pacific Cinematheque.