only magazine

↵ home

Sicko and Manufacturing Dissent

By Adam Thomas

Friday June 29, 2007

Moore than just the truth

There is no way a responsible human being can argue with the social, political and human subjects Michael Moore examines in his films. Whether it’s the lack of honesty and responsibility on behalf of corporations to take care of their employees, or the undeniable violence attributable to pervasive and accepted gun culture in the United States, or even the widely accepted suggestion that dirty tricks are at play in American politics, Michael Moore has found a way to become the voice of the left and of the everyman, representing those affected by decisions made by those more powerful than themselves.

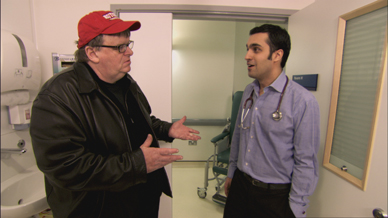

His latest film Sicko is an examination of the inarguable failure of the American-style of for-profit health care – a truly broken system that has doctors and hospitals reporting to insurance companies whose fundamental mandate is to make and save money, even at the cost of human lives. The film is a narrowly focused effort, content to tell the stories of people who have been directly effected by the unforgiving corporate mandate. It easily contends that the system, implemented by Nixon and his pals, was a plan to generate profits instead of providing care.

And Moore finds plenty of people who have heartbreaking and devastating tales to tell. People are strong-armed, refused coverage and in many cases denied necessary care because of sketchy loopholes in their insurance contracts. But beyond the simple personal stories provided by doctors, patients and heads of medical boards there is a deeper, more insidious narrative. One that includes complicit politicians and big money, and Moore binds all of this together to create a terrifying picture of fraud and deceit prescribed by those sworn to help keep people healthy.

But for all the idealism and hope he has fostered there may exist a darker side to Moore. Canadian filmmakers Debbie Melnyk and Rick Caine’s film Manufacturing Dissent presents an uneasy look at Michael Moore as a person. The film raises some interesting questions about his integrity as a documentary filmmaker and is skeptical of his self-presentation as some kind of everyman. The film follows Melnyk and Caine as they tour the world trying to get an interview with Moore, mirroring his attempts to get an interview with GM CEO Roger Smith in his film Roger and Me. As the filmmakers later discover, Moore actually had two interviews with Smith but cut them from the film for dramatic effect.

This is not the only instance of factual manipulation in his films, a point the directors seem genuinely surprised to discover. While some will take Manufacturing Dissent to be an exposing work, a film aimed at debunking and even outing Moore as a faker, the filmmakers are actually fans whose intent was discovery, not discredit: who is Michael Moore and how does he work? The fact that the filmmakers are constantly denied an interview, and are even physically removed from one of Moore’s speaking engagements generates a bizarre sense of unease about the ideas he presents and the methods he uses. Methods and presentations that have made his films some of the most popular documentaries ever made.

It comes down to a simple question about the relationship between form and function. Does the end justify the means? It’s a loaded question but integral to anyone engaged in purporting to be a truth teller, for ultimately it comes down to a question of credibility. Now Moore has openly acknowledged his work is manipulated by the very virtue it is edited and constructed. This is a point of debate that has existed at the heart of the definition of documentaries since Robert Flaherty “re-created authentic” Inuit villages and hunting sequences in his 1922 documentary Nanook of the North.

With each of Moore’s films, his popularity has grown, while his image, as the unequivocal regular Joe remains the constant thread. It’s an image that has served him well, allowing him to enter into the homes, VCRs and bookshelves of average Americans who see him as one of their own. His causes are ground level and not heady, philosophical ideologies learned in expensive Universities. Instead they are examples and stories of everyday people who find themselves being left behind in the world’s wealthiest and most powerful country.

And with his worn t-shirt, big belly and ever present baseball cap, Michael Moore wants you to believe he is one of them. While Moore has essentially revolutionised the documentary form and made it both popular and populist, and the essence of his work is without question, it would be a tragedy if his intentions were undermined because he played too fast and loose with he facts. Because if the lines between truth and construction become too blurred, the position of righteousness becomes less credible. And that would be a sad day indeed, especially with so much at stake. As much as he wants us to believe he is one of us, and as much as we want to believe, we might do well to prepare for the fact that he is just a man with a camera and nothing more.