only magazine

↵ home

In Excess

By curtis

Friday March 4, 2005

Donna Akrey, Colin Johanson, Simon McNally and Erica Stocking

Having grown up in the sprawling strip mall belt of the Fraser Valley–Chilliwack to be exact–it seems a new Dollar Store pops up every time I go back to visit. Harsh fluorescent lights illuminating toxic, Chinese-manufactured plastic and stinking of a mélange composed of noxious perfumed soaps and cheap rubber tennis balls, the contents of these stores are always one step away from the dumpster. At the stink-end of the mall’s metaphorical large intestine, the Dollar Store is the perfect symbol for a culture that buys objects the equivalent of shit, a waste byproduct of consumption. In Excess, currently up at the Helen Pitt Gallery until March 26, 2005 and presenting the work of four young artists, deals with these issues by not only looking at this culture, but reflecting it by recycling or reproducing the material byproducts of said culture.

Calgary artist Donna Akrey uses the image of a real estate agent from her home town carefully cutout out of hundreds and hundreds of identical flyers sent out by post, to construct Business Mandala. Meticulously constructed at six and a half feet, the exact dimensions of a true Buddhist Mandala, Akrey’s piece uses the tropes of the meditative shape to fashion a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the ubiquitous flyers and junk mail pumped out by businesses looking to draw the aimless into their capitalist web. A pleasing shape at a distance, the hideousness of the piece is revealed up close as one realizes that this balding, bespectacled realtor and his encircling clones only represent a small fraction of individuals contributing to the cookie-cutter subdivisions of Calgary’s increasing urban sprawl.

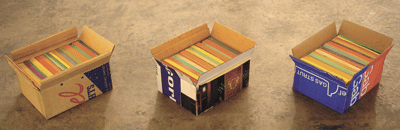

Recycling used objects such as audio and videocassettes and paperback books, Simon McNally references the art historical background of the minimalist cube while assembling objects representing both labours of love and of vacant consumerism. The most successful combination of these is a cube he’s made out of a variety of cassette tapes: from mass-produced and far-removed popular and classical music albums to more tangible mix tapes, it’s almost impossible to imagine the cumulative time and effort that went into producing these recordings. McNally’s Cassette Cube is reflected in three of his wall pieces titled, Paragraphs, which are the spines of cassette tapes arranged on pieces of paper behind glass. Mixed in with classics like Metallica’s Black Album are personalized, hand-written blank tape spines, the eclectic range of titles and the way the spines are stacked one on top of another echoes the 50 cent tape sections found in almost every second-hand store giving a sense of pathos and humanity to these objects of popular culture.

Similar to McNally’s cassette tape pieces, Collin Johanson uses pathos in relation to popular music as he himself attempts to recreate the cover image of Paranoid, Black Sabbath’s seminal heavy metal album, in both a photograph and accompanying video. Responding to a particular type of consumer–that of the ‘fan’–Johanson dresses up as the pseudo-medieval warrior of the Sabbath cover, except instead of sword, shield and armor he wields a sharpened stick, a trash can lid and situates himself in a suburban setting. Johanson’s Paranoid reflects the attempt on the part of the fan to remove himself from his role as a passive consumer and become an active participant.

Sharing a naïve sense of hope, Erica Stocking’s contributions to the show are all intrinsically linked together through debt, luck and a blind faith in wish fulfillment. The first is an ongoing series of credit cards she has used to pay for food, travel and any other expenses incurred leaving behind no physical object; some are paid off, some are not. Each one of these cards represents a chunk of her life at a certain period of time, simply titled by the amount each has accrued.