only magazine

↵ home

Emily Carr

By Asher Penn

Wednesday November 15, 2006

Dead White Woman of the woods

When I was in high school I remember almost never going to the top floor of the art gallery. I knew what was up there: The museum’s pride and joy, “the largest collection of Emily Carr paintings in North America.”

Compared to the hip, political, humorous, visually stimulating work that was usually available on the main two floors, Carr’s work was everything that I wanted to avoid in art. Walking through a room filled with her painting was akin to a muddy nature hike with your parents–boring and lame. And while Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keefe have endured in art history as iconic painters, Emily Carr has been forgotten, even in my school textbooks. International art historians were bored to tears by her creations, and saw no merit in perpetuating her “legend.”

Ten years later, Emily Carr’s presence still looms large nowhere but in Vancouver. The VAG has moved the collection to the bottom floor, and accumulated more works from various collections (including Bryan Adams’) to create the most comprehensive Emily Carr exhibition in history: “New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon.” The show presents Emily Carr as she has never been seen before.

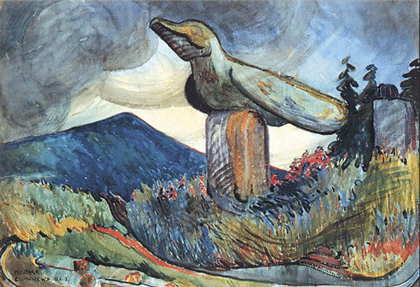

First you see it in the context of her national debut, “West Coast Art Native and Modern.” Here. Carr’s paintings of totems were juxtaposed with the real thing and shown with unaccredited masks, blankets and sculptures made by First Nations artists.

Next, Carr’s work is presented in the modernist style, showing her acceptance into the Group of Seven, and the development of her signature semi-abstract painting style. Finally, the curators applied a more contemporary approach by presenting Carr’s work as it relates to the history of British Columbia’s forestry and tourism industries.

Despite this attempt to show Carr in a new light, the work feels un-changed. It makes you wonder why Vancouver’s largest art institution is so hung up on this dead white woman of the woods?

Perhaps the answer is to be found within Vancouver itself. Emily Carr was the first artist in BC to see the indigenous cultures and natural landscape of BC as something with artistic merit. While Carr was sad to see these things slowly destroyed at the hands of development, her art’s position was romantic and apolitical–preserving these elements through her art and writing, while doing nothing to alter their demise.

Emily Carr is a cultural icon because she pioneered the identity that the Pacific Northwest now calls it’s own. A soft colonialism that respects history enough to keep it alive on a Western iron-lung; an ideal that begins with conservation in mind but ends up abstracting its source until it is nothing but estranged design. In the show’s last room we are shown Carr’s hook rugs and ceramic pots with First Nations’ decoration, recontextualising tradition to adjust it to the invading culture. First Nations never made hook rugs and ceramics. Those little ash trays are reminiscent of t-shirts from the Museum of Anthropology, or long house designs on the facades of Whistler bars. Emily Carr’s figurative paintings of totem poles are the blue-prints of decoration for a Gastown tourist trap. Her paintings of trees are bike paths in the endowment lands. She is the first person to present Vancouver as we all experience it today: a city that celebrates First Nations’ art without supporting the First Nations people. The beautiful trees of the Sea-to-Sky Highway block the view of the miles of clear-cuts.