only magazine

↵ home

Mexican Labour

By Sean Condon

Sunday October 1, 2006

BC Agriculture’s Immigrant Secret

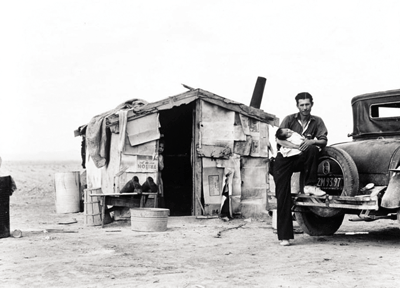

In an industry that has a history of treating its employees like fertilizer, British Columbia’s farms are now being fueled by cheap and exploited Mexican labour.

Over the past year, the number of Mexican farm workers in the province’s Okanagan and Fraser Valley doubled to 1,238. They come into Canada through a joint Mexican/Canadian government program that gives them a temporary visa to work one of the worst jobs in the country, with little rights or protections.

“The Mexican workers are coming into a sector that already has a lot of problems in its treatment toward workers,” says Erika del Carmen Fuchs, an organiser with Justice for Migrant Workers in BC. “It’s seasonal work and very low paying… [But because] the Mexican workers are isolated it makes them highly exploitable. They don’t usually get any [health or safety] training, and even if they are trained, they don’t understand it.”

Migrant farm workers have been coming to Ontario through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program since 1974 because less and less Canadians want to work 13-hour days in the sun for minimum wage and possibly lose a limb. But it wasn’t until 2004 that B.C.’s agricultural industry (aka Gringo bosses) convinced the federal government to expand the program out West. As part of the agreement between the three levels of government Mexican workers are guaranteed a minimum of $8.60 an hour and can stay in the country for a maximum of eight months.

The Mexican and Canadian governments are rolling in the hay together over how successful the program has been since it offers Canadian farms cheap labour (and the Mexicans have to go home at the end of the season) and it pours a large amount of money into Mexico’s economy through remittance payments.

But the program has been heavily criticised in B.C. for its lack of labour protection, minimal health coverage, and shit-standard housing. There was a case last year where 50 Mexican men were found living in a two-storey house and two trailers that had no heat, one washing machine, two small kitchens, and water dripping through the floor (Welcome to Canada, mang).

Although other provinces take care of housing inspections, the B.C. government does not. The workers are also not covered under the province’s Medical Service Plan (MSP) – they have to set up their own private medical plan. Many workers have complained about having to work long hours, not getting paid, or having their injuries ignored. Workers who speak out and complain, have been fired and sent home – including one worker at the Golden Eagle Farms, which is co-owned by Canucks owner Francesco Aquilini.

“The program grew too fast and no one has been prepared for the growth,” admits Mercedes Vazqez, vice-counsel at the Mexican Consulate-General’s office in Vancouver, which handles workers’ complaints.

However, Vazqez insists the program is improving as it ages and that the farms and the government are getting accustomed to the rules and regulations. But one of the biggest problems with the program is the lack of accountability. Since the program is run by three different governments, responsibilities are passed around to each body (workers complain that the Mexican government consistently side with the farms). A spokesperson with Service Canada, the Canadian government body that runs the program, says it only looks at labour issues and would not comment on any of the broader issues.

The Canadian government is planning on conducting a review of the program at the end of the year, and will talk to different governments and farm owners. But it will not actually talk to the workers themselves. Despite its problems, Fuchs says the program has to keep going because of Mexico’s poverty, but that the different governments needs to start listening to the Mexican workers and improving farm conditions in general. Until then, B.C.’s farm industry will continue to get away with some rotten labour practices.