only magazine

↵ home

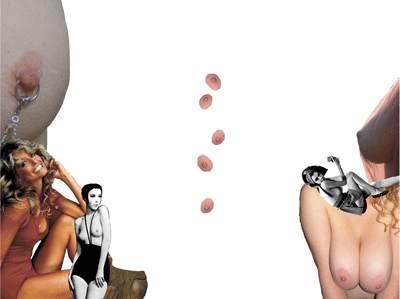

A Brief History Of The Nipple

By Amil Niazi

Tuesday November 15, 2005

The once-holy symbol of female fertility and sexuality has become irrelevant in modern society; the breast is now less useful as a sexual provocateur than a conduit for milk. Men are no longer fazed by the current shapes and sizes and women go to extremes to distort mammalian reality. But somehow we’re still horrified, mystified and consumed by the breast’s best accessory, the nipple. Nipples are a cultural landmark and the zeitgeist of generations; they serve as pointers of where society is and where it’s going.

During the Renaissance a heavy bosom was a sign of fecundity and good health, but the best way to turn a billowy mound into alluring femininity was to rose the nipples in order to present a picture of enhanced arousal. The poems of men like Robert Herrick spoke of ivory breasts with reddened points perched atop.

Have ye beheld (with much delight)

A red rose peeping through a white?

Or else a cherry (double graced)

??Within a lily? Centre placed???

Or ever marked the pretty beam

A strawberry shows half drowned in cream?

Or seen rich rubies blushing through

A pure smooth pearl, and orient too?

So like to this, nay all the rest,

Is each neat niplet of her breast.

The masters painted only the most pleasing, mothering breasts with rosy centres. Through an era of renewed creativity and, more importantly, of renewed life, nipples emerged as the symbolic bounty of an abundant epoch, a time of replenishment, resurrection and reproduction. But with every swell there is an ebb, and as Victorian prudency was ushered in, the nipple was escorted out of the public and even private eye.

Suddenly women were not just covered, but wrapped up. Underclothing had its own underclothing and fashion was meant to be torturous and sexually oppressive. Victorian principles embraced decorum, classist social structures and Christian morals. This was a time when men were viewed as seducers and women as victims, when, in the interest of this morality, sex was intellectually abolished. The nipple, naturally, was considered next to demonic, a symbol of the kind of lewd concepts that lead to evil. It’s also interesting that during this time women began to more actively explore and mimic male sexuality by superficially changing genders, as an avenue to express sexual desires. Genitalia were subverted and the nipple, following suit, was physically and culturally bound.

Not just a relevancy marker, the nipple has also been a divining rod in situations where social mores faltered and failed. After the devastation of WWI grey was the thing, for moods, for politics and for fashion. In a wave of nouveau capitalism however, the undergarments were shed, the nipple revealed and the roar of the twenties thundered in. Josephine Baker erased colour lines, trumpeted a subtle but entirely beguiling sexuality and lent the image of her body to hundreds of writers, painters and musicians. In her portraits photographers were captivated by her ability to mesmerise men and women with nothing but her smile and a series of well placed pearls. When not holding up the American immorality curtain, Baker was an undercover agent for the French Resistance. This heaving opulence was also captured in the way the bejewelled gauze clung to the alert bodies of Louise Brooks, Anita Loos, and Coco Chanel. The potent politics and pioneering styles of these aggressively modern women were held up by their breasty centres. An entire generation of Gatsby’s respected and reviled both themselves and their superficial decadence, but it was the nipple that emerged as the hero.

And it remained quietly in the background of the slowly growing women’s movement, though suffered entropy in the 1950’s when the shape of women’s breasts were lent exaggerated conical shape by the heavily padded bras of the time. But like all movements, it found its climax when the swingers of the 1960’s did away with bras and designers moulded clothing around the bare breast, not the garments holding them at bay. Rudy Gernreich’s infamous one-piece bathing suit shocked the world when it turned out to be topless. Artfully constructed to reveal both breasts, the bathing suit covered more of the body than an average bikini, but was scandalous because of the appearance of the nipples. What became obvious and subsequently fascinating was the idea that it wasn’t nudity, until there was a nipple. The bathing suit sold 3000 units to women across America, eager to shed the restraints of the past two decades. Gernreich also designed the first transparent “no bra” bra, which the leading bra manufacturers still base their most popular models on. It is designed to mimic the natural shape of the breast, with the nipple front and centre. The androgyny of the 60’s also allowed for men to revel in the emergence of bare sexuality. The now dreaded, but initially heralded, Speedo was everywhere on European beaches. Men’s clothing became lighter, left open down to the pubic bone and as clingy as women’s blouses. The 1960’s and 70’s were a celebration of the human form at its most raw.

The natural course of fashion is to jump between both extremes of virginity and brazen sexuality. Politics do much of the same, only their topless bathing suits are abortion rights and same-sex marriages. A careful eye sees the social emergence and disappearance of the nipple as a telltale sign of an era. The eighties were about power and selfish decadence, shoulder pads and cocaine. Breasts were used to market manipulation, but nipples were second-class citizens. This wasn’t about sensuality and fertility, but about domination and gender dynamics. And then one-day nipples appeared on mannequins. This was a huge stepping stone for the body reality in fashion. We finally accepted the state of our figures as marketing truths. Clothing was built for actual women as opposed to dreams of globular automatons. But our modernity is draped in confusion. While mannequins were allowed to sport nipples, models on the cover of magazines had theirs airbrushed out. Actresses in big-budget films were also stripped of their headlights and one had to wonder whether they had simply donated theirs to the storefront dolls. David Letterman is famous for having kept his studio quite cold, encouraging activity in the nipples of his guests. For women who don’t feel like they have enough nip, you can also purchase paste on pasties, just in case the weather is forgiving. We’ve gone from nipple-phobic, to nipple-centric in just over a century. Always carrying the weight of generations with each sighting.

A classic Seinfeld episode centred on the accidental appearance of Elaine’s nipple asked the question, “When is it sex?” The answer: when the nipple makes its first appearance. This also appears to be true for social change, physical revolution and moral editing.

Collage by Sarah Cordingley