only magazine

↵ home

Rebel Yell

By Adam Thomas

Friday September 30, 2005

Peter Watkins‘ ”Punishment Park“

It’s a telling reflection that a filmmaker whose work constantly challenges the political status quo and even the very fabric of conventional cinema should find his work relegated to almost obscurity. Even now British filmmaker and documentarian Peter Watkins’ work is largely unavailable in North America, despite the fact that his film The War Game won the 1966 Academy Award for best documentary. Forced to work and seek financing from liberal European countries like Sweden, Denmark and France, Watkins continues to make films that challenge both the notion of genre and the accepted paradigms of political power. The recent DVD release of Punishment Park (1971) is perhaps the most revealing example of his work, a film that demolishes the boundaries between fact and fiction and presents the brutal cultural divide that began in the 1960’s.

As much a social analyst as he is a filmmaker, Watkins writes about the hierarchical and detrimental nature of public media from television networks to Hollywood, and his films largely explore the cinematic and cultural relationship between control, power and truth. By using hand held cameras and having non-actors look directly into the lens, Watkins manipulates the language of the documentary, allowing him to create realities that are strangely illusive but frighteningly believable.

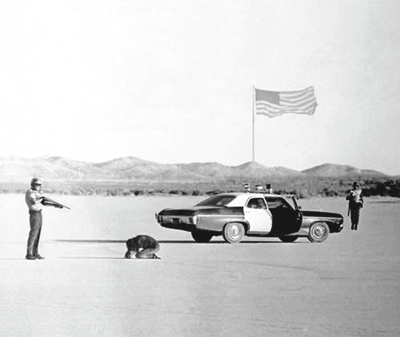

Punishment Park is his examination and contemplation of the delicate political fabric of contemporary society, and it sent a controversial chill down the spine of audiences across the US where many challenged it as being anti-American. Set in a near future, circa 1971, Punishment Park begins with a written introduction that reads a lot like a section from the Patriot Act but exists in the context of the social turmoil being experienced in the US in the early seventies. The film presupposes that the President (Nixon), in an attempt to stamp out the rising antiauthoritarian movement, enacts a section of the 1950 Internal Security Act assigning himself executive power to be able to preventatively detain any thought to be likely as to “engage in future, possible acts of sabotage.” Denied any formal legal proceedings the detainees are presumed, then found guilty by a make shift tribunal of local citizens. The newly convicted are faced with two choices, long prison sentences or three days in Punishment Park.

Bear Mountain Punishment Park is a zone created to provide law enforcement and National Guard forces a training ground against those who would seek a violent overthrow of the United States Government. The three-day sentence consists of a 30-mile trek across the desert, without food or water, while avoiding capture, to a solitary outpost topped by an American flag. If successful the prisoners will be pardoned. The authorities however, during the course of the sentence are at liberty to use any force necessary to apprehend or stop them. Here the film alternates between the hearings of other accused and the actuality of Punishment Park. It is a gritty and bitter political nightmare as those faced with punishment vehemently accuse their accusers of greater crimes. Almost entirely improvised, the film lives, breathes and registers as a documentary but as one from an all too close, parallel universe. We watch as the prisoners who rapidly descend in to violence are met with superior violence and as the inescapable frustration of political and humanist values are slammed into each other and torn apart. Despite being over 30 years old, Punishment Park remains a tangible, but hopefully paranoid possibility.